“So much of who we are is described by the choices we make. More than anything, I am proud that we chose to show up and give our best effort to what ended up being simultaneously one of the most challenging and most joyful things that either of us has ever done.“

Nora Randolph, FBRA Girls Outdoor Program Director

For FBRA Girls Outdoor Program Director Nora Randolph, many outdoor pursuits come quite easily. However, her adventure on the John Muir Trail this past summer was NOT in that same “easy” category. Here’s Nora’s recount of a journey that pushed her to her outer limits in the best possible way:

When we got the John Muir Trail (JMT) permit back in January, I told my students that I had just gotten the equivalent of Taylor Swift concert tickets for backpacking. (According to my unscholarly research, T Swift concert tickets and JMT permits both have success rates of 2-3%.) They were impressed, but questioned the prudence of spending three weeks of my summer carrying a heavy pack up and down mountains and sleeping on the ground. Luckily my husband Eli and I were undeterred by prudence and we started to plan what would turn out to be the adventure of a lifetime.

By the time we scored our permit on January 20, California had already been hit by nine atmospheric rivers, with three more to come in the following months. By April, the Sierra had received 200-300% of its average snowfall, according to the California Department of Water Resources. By that time, Eli and I were following California’s snowpack reports closely and feeling more than a little nervous. We had purchased our flights and booked accommodations at either end of our trek. We had borrowed two very nice food dehydrators and were deeply entrenched in preparing a month’s worth of ultralight, compact, calorically dense meals. Eli had somehow managed to get a whole month off of work. Most importantly, we were desperately looking forward to an adventure.

The idea to go hiking had been born of nostalgia and frustration. Remember when we lived in our Honda Fit between Outward Bound seasons and spent the whole winter rock climbing out west? Remember when we hitchhiked through Chilean Patagonia for two months and backpacked along the southern ice cap? Somehow the finer details slid away from us. (Remember when we had no personal space and took weekly showers at the climbing gym in Las Vegas? Remember when we couldn’t get a ride for days and were stranded in rural Chile in the rain until a dump truck picked us up?) We were stuck. Who are we without the freedom and uncertainty of adventure? Where is the wild and beautiful unknown? The John Muir Trail (JMT) is 220 miles of wild and beautiful landscapes – a promise of adventure indeed.

So we read and researched, dehydrated and rehydrated, mapped and mapped and mapped some more. Where will we pick up our food resupplies? How will we fit ten days worth of calories into a bear canister? Why do blueberries take so long to dry? These were the questions that haunted our months of intense preparation. And the most important question: should we even try? What we originally imagined to be a simple, if strenuous, vacation for experienced backpackers was quickly turning into a serious mission through snow and swollen creeks. We committed. We borrowed ice axes and crampons from friends and dedicated yet more hours to poring over maps, learning every possible evacuation route and alternate itinerary.

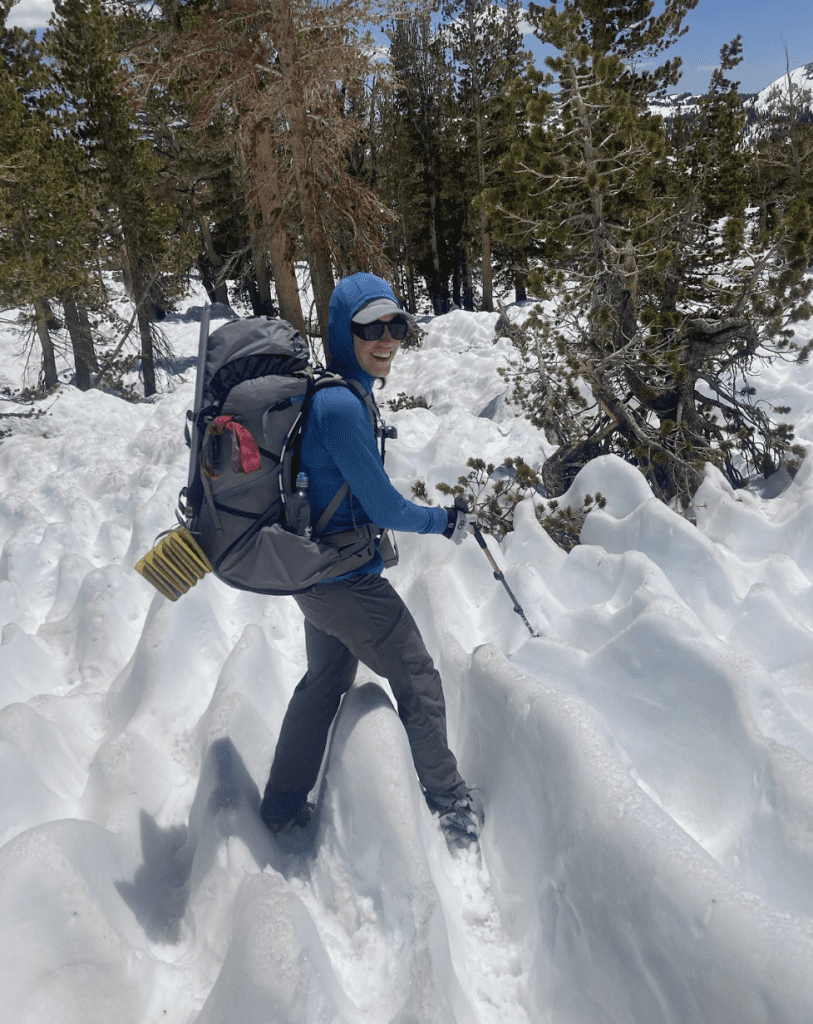

And so when the hour arrived at the end of June, we started our hike from Yosemite Valley. In the first four days, we hiked just over half a mile per hour. The snow was endless. In the forest, it rose and fell in steep tree wells that tripled our distance with their ups and downs. Above tree line, the snow was slushy and cupped in deep troughs and fins that tripped us up and twisted our ankles. We soon learned that these are called “sun cups” and that they would be the theme of the trip. The offline GPS data we had downloaded “for an emergency” turned into our primary navigation tool, since we could not see the trail under the snow. Our feet were constantly wet and I got deep, painful blisters on the balls of my feet. We were moving so slowly that we were afraid we might run out of food before we got to the next town. It was difficult to focus on the beauty around us – we woke up, hiked all day, and collapsed into the tent in exhaustion. Our clothes were damp and our spirits were damper. On the fourth evening as we ate dinner on the trail with several miles yet to hike, we decided that something had to change.

Instead of picking up our prepacked resupply bucket trailside as we had planned, we walked all the way into Mammoth Lakes. It was surreal to surface from our slog, having hiked ten miles already that morning, at the Mammoth ski area where hundreds of people were zinging down the mountain on the 4th of July weekend. There we stood, covered in dirt with all our belongings on our backs, amidst people skiing in bikinis and children tumbling around a bouncy house. In town, we found a laundromat and a shower and a grocery store to bulk up our bucket provisions. Clean and fed, we faced the facts. We would probably not reach Mt. Whitney – the JMT’s southern terminus – in the time we had. We were moving more slowly than we thought possible, there was no end of snow in sight, and the creeks were rising, which meant we were spending more and more time bushwhacking in search of safe creek crossings off trail. But the goal had never been to make it to Mt. Whitney. What we needed, really, was a beautiful adventure.

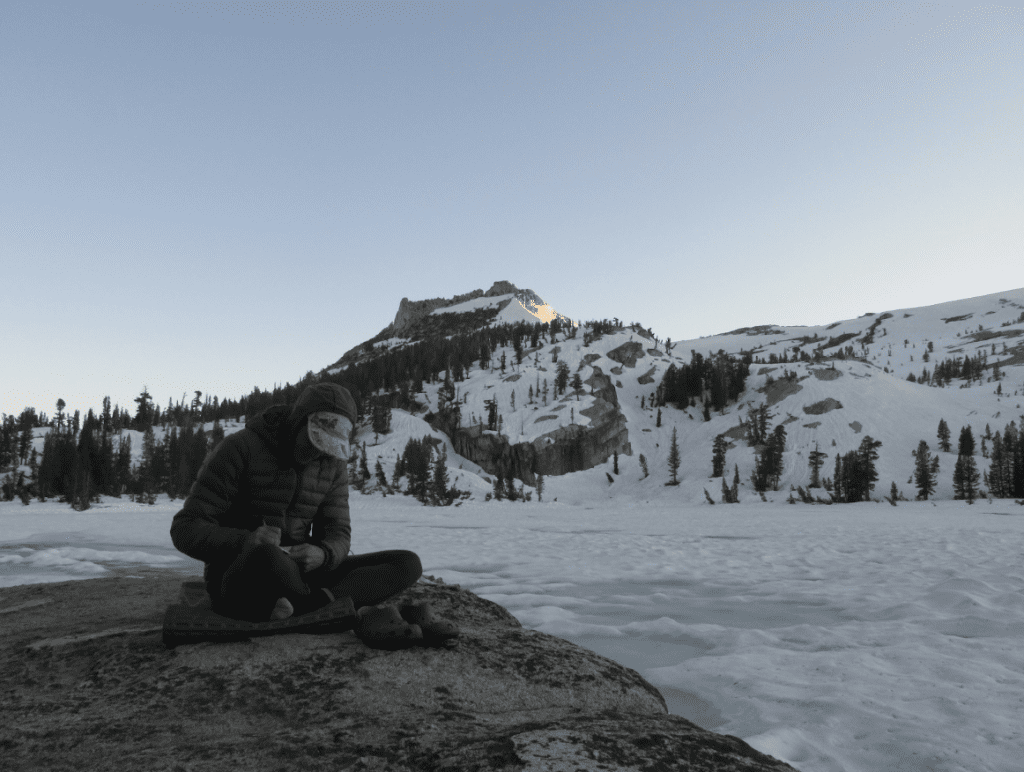

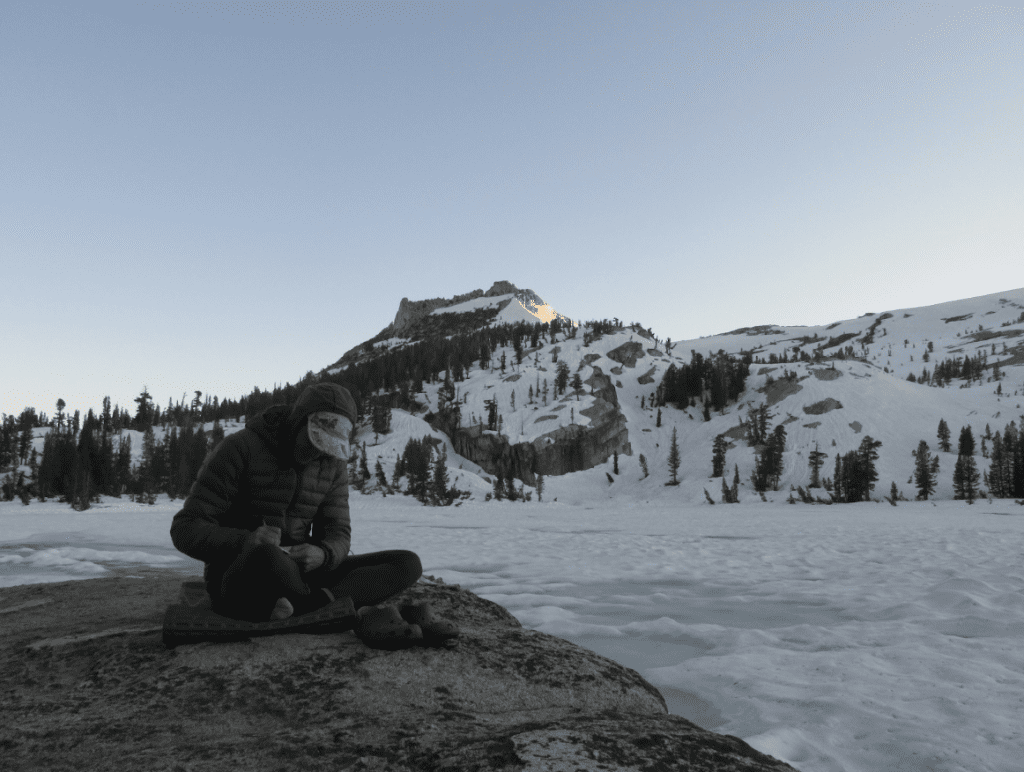

We started waking up in the barely-morning hours before dawn. Starting early, we could take advantage of several hours of travel while the snow was still frozen firm, moving quickly without slipping and falling in sun cups. Our new routine was this: wake up at 3, tape up my blistered feet, break down camp, coffee and first breakfast at 3:45, start hiking around 4:15 under the expansive Milky Way, watch the mountain tops turn pink and gold at 4:45, second breakfast at 5 in full daylight, and then a push to cover miles before the snow softened in the sun around 8 am. As soon as the sun hit our skin directly, put on sunscreen, glacier glasses, sun gloves, and hats. Lunch around 8. Snacks all day. The second half of the hiking days was the hardest – we would slide over sun cups and hedge our bets on the last snow-free campsites… could we push another mile and still find somewhere to sleep? And then around 3 or 4 pm, we were done! We could set up camp and relax, rinsing out our sweat-stained clothes in the heat of the day and knowing they would be dry by morning. I unwrapped my feet and spoke words of encouragement to the new skin on the edges of my blisters. We made miso soup and wrote in our journals, recording mileage and trail conditions. We enjoyed the gourmet dinners that we had spent so many hours preparing in the spring. We went to sleep each night around 7.

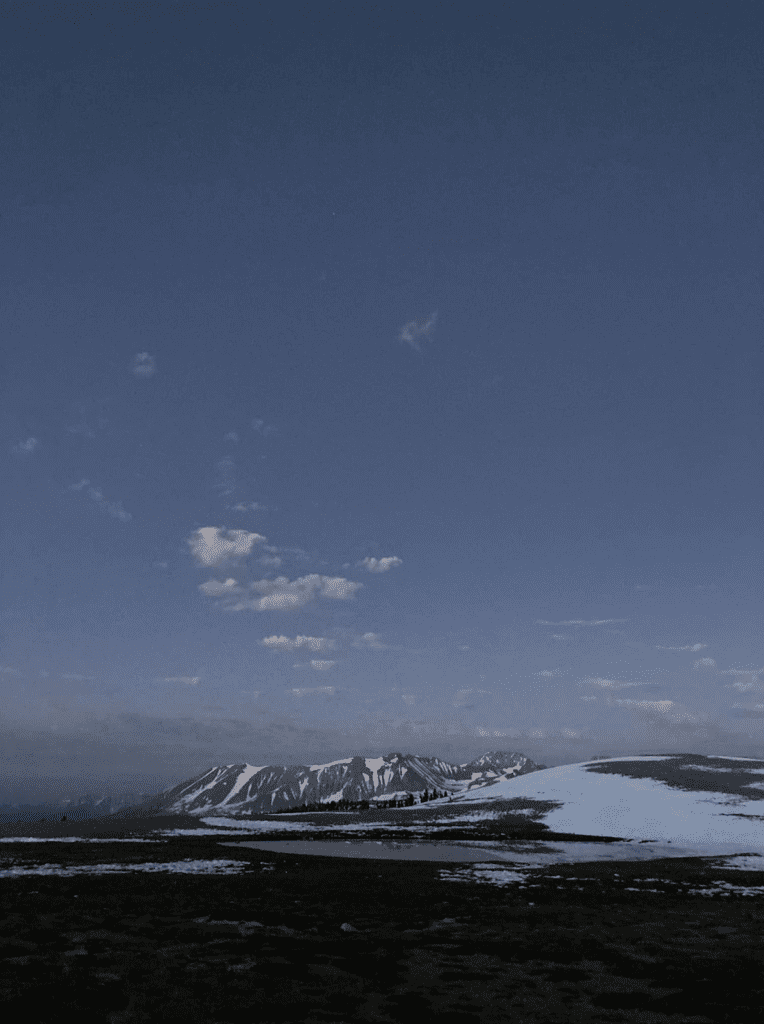

We timed our whole itinerary around the melting snow. Daytime temperatures were in the 80s, while overnight it would be in the 30s-40s and the rapid melting would stop for a few hours. Walking on the snow and crossing creeks were both persistent reminders of changing conditions, since the creeks would rise and fall as much as 18 inches between day and night. We needed to cross both steep snowy passes and rushing creeks early in the day to have any sense of safety or success. So we mapped out our new plan, making camp each night as close to the next pass or creek crossing as we could while still below tree line, so we could sleep on dirt rather than snow. Creeks were easier to time: earlier was better. Often the crossing at the trail itself would be too deep and we would need to walk off trail for up to a mile upstream, looking as we walked to find a spot where the current slowed or the creek divided into braids. We arrived at most of our serious crossings before 6 am. Occasionally there were logs to walk across, but usually we would sit down and remove our socks and insoles before lacing our boots up tight in preparation for slippery footing and strong currents. Picture us: the sky is beginning to lighten and we are mid-creek with a torrent of water hitting the middle of our thighs. We are a four-legged unit, holding each other’s packs and moving one foot at a time, talking to each other, “Hold on, I’m set, okay go… are you set? Yes, I’m set, okay go…” We are wearing raincoats and warm hats, pants rolled as high as pants can roll, socks tied to the tops of our packs. Only once as we crossed below a frozen lake were we surprised by a chunk of ice colliding with my legs – Eli shoved me forward as I fell back, and we stayed upright. On the other side, we would race to put on socks and wring out our boots before putting them back on in the chilly morning. On one occasion, to avoid a bridge that had been mangled by the weight of winter snow, we followed the advice of a northbound hiker we had met a few days earlier and scrambled up the side of the canyon, gaining 1800 feet over the trail below, then scramble-hiked several miles across the low-angle canyon wall before descending.

The steep passes were a little trickier to plan. Hard snow meant efficient travel, but we needed to be able to pierce it with an ice ax – if either of us slipped, we didn’t want to find ourselves speeding down a sheet of ice with no way to slow down. On pass mornings, we would start early as usual, crossing the snow fields and picking our way up the crusty sun cups to the top. If the snow on the south side of the pass was not soft enough to kick steps into, we would wait for the sun to catch up. Then we would carefully descend, knowing that we were in for a long afternoon in the snowfield below.

We started picking up speed – we traveled slightly faster than one mile per hour each day and we took no zero-mile days. We started encountering more and more exposed trail, which let us move upwards of two miles per hour. As a joke, we called any day with a few miles of exposed trail a “rest day” since we didn’t have to work as hard for our progress. Our so-called rest days were our highest mileage days, of course. We picked up our second resupply on schedule and then our third. Our third resupply was the decision point: was our hike over, or could we make a push to the end? When we met Rae Lakes backcountry ranger on the trail on day 18, she was surprised and impressed to hear that we had come all the way from Yosemite. It was mid-July and she had not met a single JMT hiker yet. She told us that the conditions ahead were less snowy and that the creek crossings to come were smaller than what we had already managed. “It seems like you did the hard part. Now you just have to finish walking.” We were surprised to look at our maps and see that we had a chance after all. We planned our days out carefully, knowing that “just finish walking” also meant traversing 13,000 ft Forester pass and climbing Mt. Whitney.

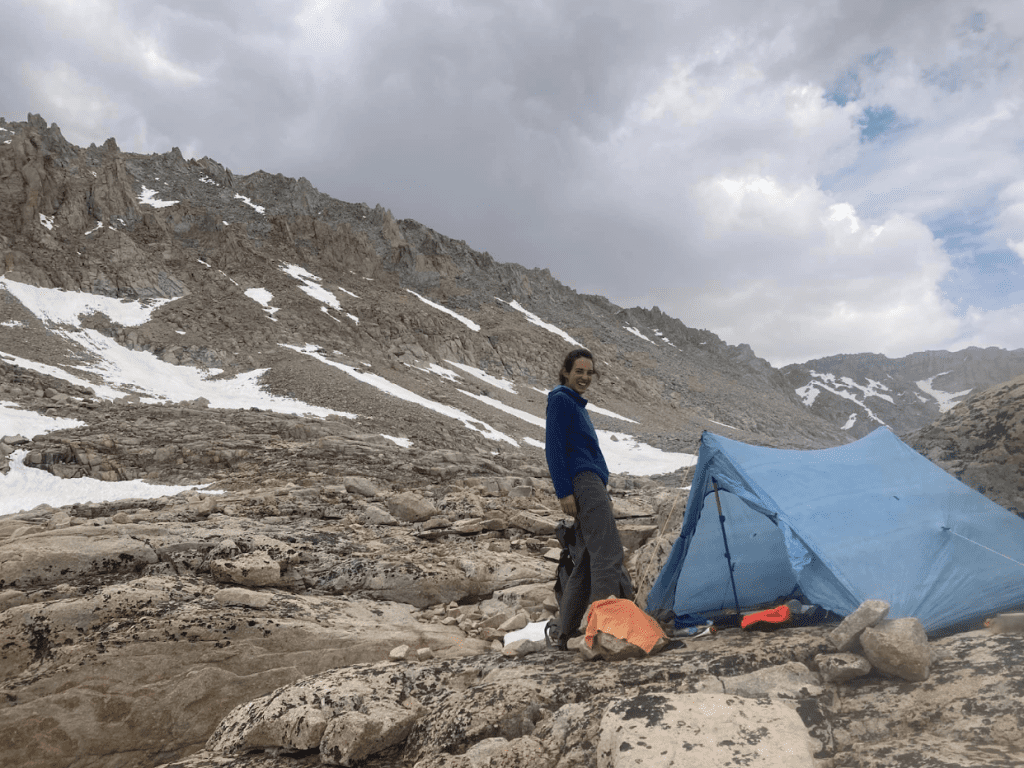

We timed our Mt. Whitney ascent for sunrise on day 21. We camped the night before at the last single tent-sized patch of exposed rock in the middle of a snow field below the Whitney ridge. We tried to sleep from 6pm until 11:45 pm – I think I slept maybe 30 minutes. In the early morning hours we carried our packs up to the ridge where we left them, taking only day packs up the spur trail to the summit. Most of the switchbacks were melted out and exposed, but there were two spots where we opted to scramble up between boulders to cut switchbacks that were still under deep steep snow. Hiking and scrambling a steep mountainside at 14,000 feet in the full darkness on very little sleep were some of the most nerve-wracking hours of my whole three-week experience. Eli had slept considerably more than I and he took point on navigating and making sure I was upright. Miraculously, we had the summit to ourselves for the sunrise. The JMT as a whole and Mt. Whitney in particular are both well traveled and we had expected to share the trail even on this low-traffic year. Yet we had not shared a campsite a single night. There were several days that we saw no other people. And here we were, at the highest point of the contiguous 48 states at sunrise, with not a soul in sight.

It was beautiful: sunrise on Mt. Whitney and daily sunrises on the trail, starlit breakfasts, jagged mountains, massive pines, slabs of ice melting into turquoise lakes, creeks that rushed and fell and disappeared under massive and fragile bridges of snow. And it was certainly an adventure. Eli and I used every skill that we have collected in our combined decades as outdoor professionals: trip planning, navigation on and off trail, decision making, climbing and scrambling, swiftwater wading, tenacity and courage, terrain assessment, wilderness first aid, bear chasing, communication and compassion, and so many more. Remember when we hiked over 200 miles through the Sierra? Remember when we realized that we were going to sit on top of Mt. Whitney after all? Remember when we finished the hike and got a free pancake the size of a hubcap at the Whitney Portal Store?

So much of who we are is described by the choices we make. More than anything, I am proud that we chose to show up and give our best effort to what ended up being simultaneously one of the most challenging and most joyful things that either of us has ever done. And I am already excited for whatever adventure will be next.

Nora’s JMT Photo Gallery: